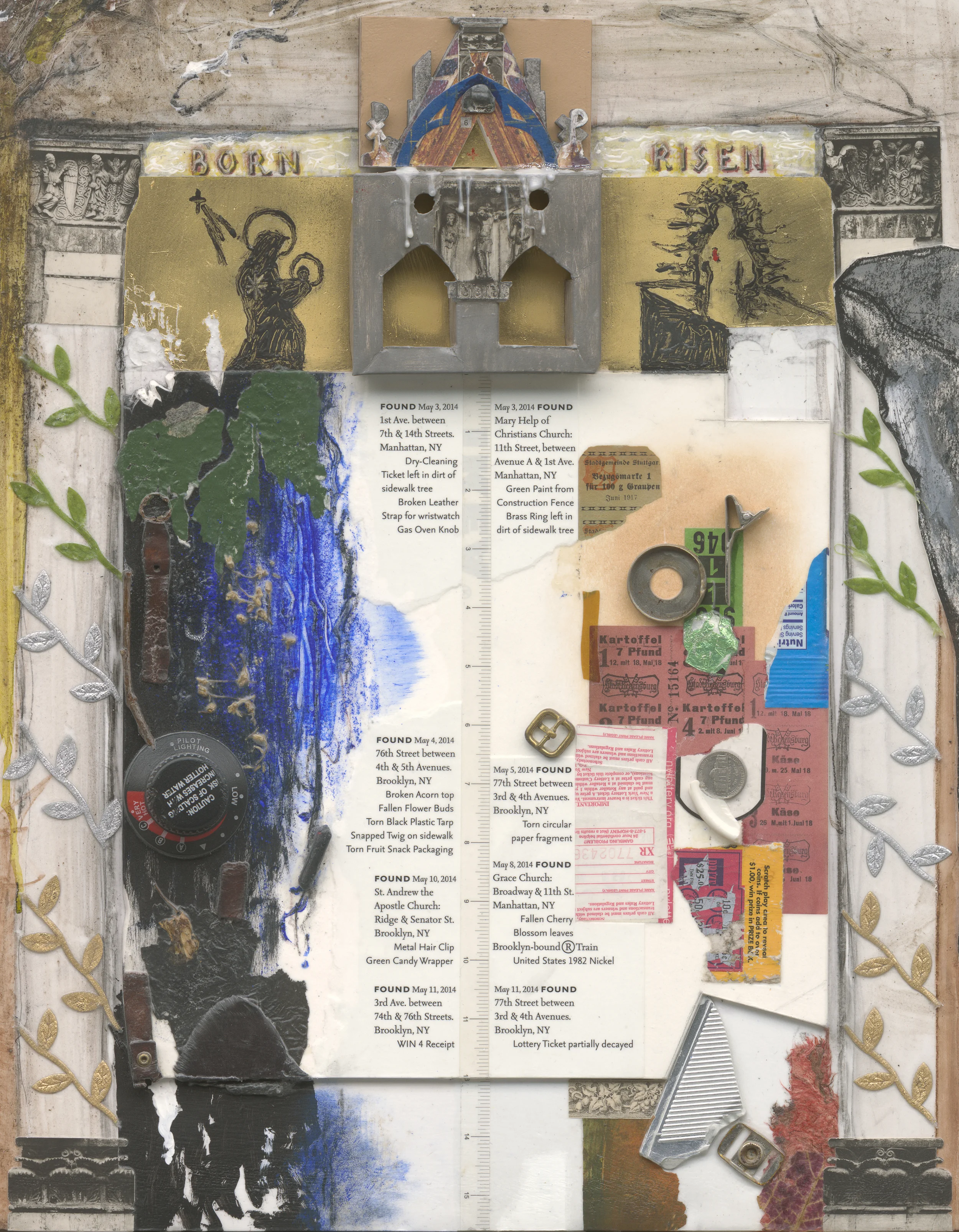

Mixed media assemblage on museum board, 2020

10 x 10 inches

Cut signatures: Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, Klaus Scholder, Michael Phayer, Dietrich Goldschmidt, Karl R. Stadler, Hermann Bahr, René Marcic, Erik Peterson, Franz Werfel, Anton Pelinka, and Friedrich Heer

“Hitler represented the secularized baroque version of Catholicism as expressed nowhere more clearly than in Austria. Before his family moved to Linz, Hitler spent two years at a monastery school in Lambach, run by Benedictine monks (Heer 1968: 21 f.). He was influenced by his father’s anticlerical attitude as well as by his mother’s traditional piety. Nothing is known about the young Hitler’s church attendance or other religious activities after he left his Upper Austrian home and moved to Vienna, but Hitler never openly broke with the church he was born into. The neo-pagan tendencies others in his party followed were not his own.”

Anton Pelinka, Austria: Out of the Shadow of the Past (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998), 179.

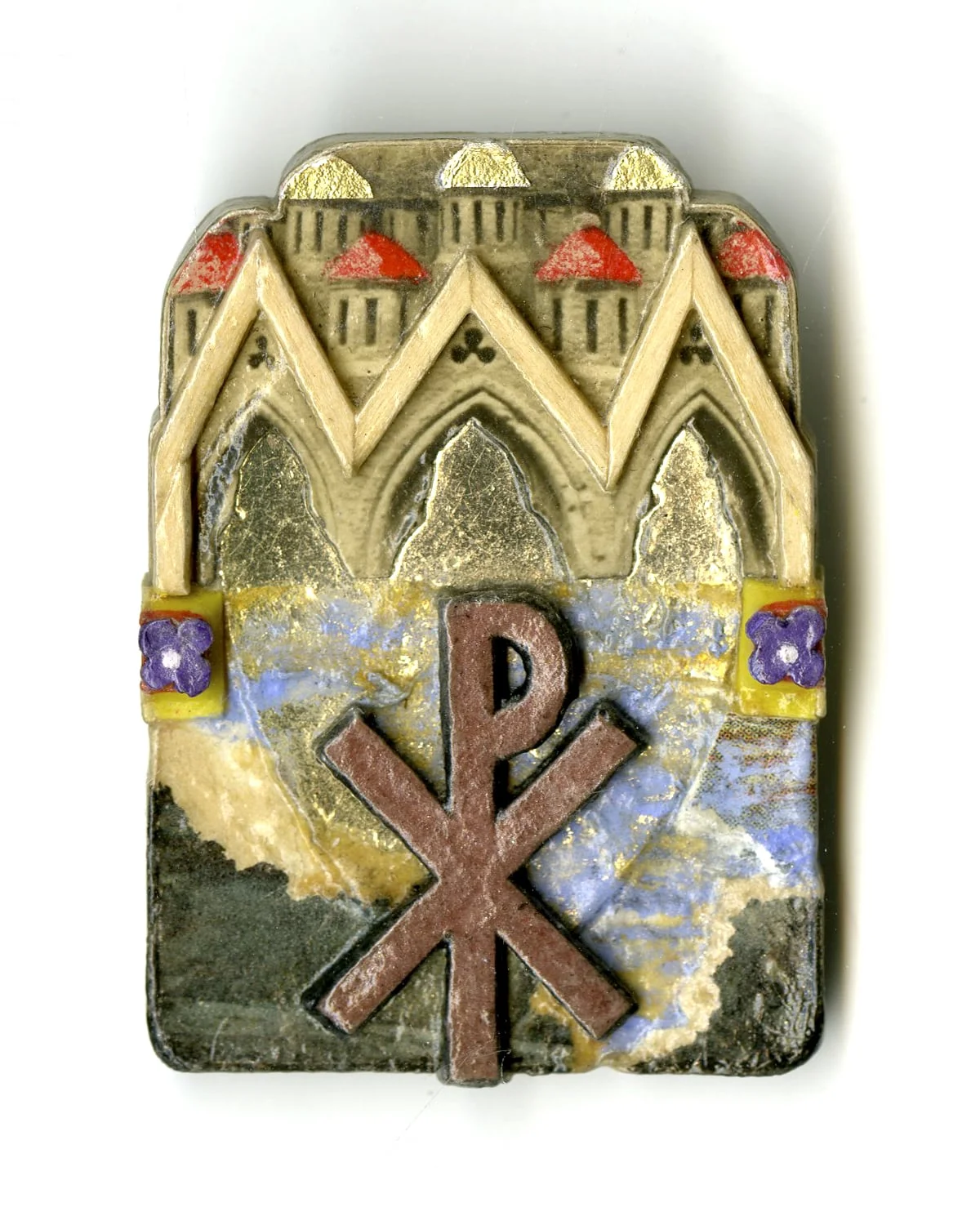

“Im Stile bayerisch-österreichischer Andachtsbilder malt später ein Maler den Knaben Adolf kniend vor dem Stiftsportal. Ansichtskarten zeigen den „Führer“ als Ritter St. Georg, über den Drachen reitend - vom Wappen fließen Strahlen auf seine ausgebreiteten Hände. Der Knabe Adolf als ein kleiner St. Franziskus oder Aloysius, als einer der Knabenheiligen: das ist Kitsch, religiös-politischer Kitsch. Hermann Broch sieht den Kitscherzeuger als Verbredier an, Adolf Loos sieht im Ornament - Hitler liebt das Ornament - ein Verbrechen. Eine gewisse Gefühlslage des Knaben, der sich „oft und oft am feierlichen Prunke der äußerst glanzvollen kirchlichen Feste zu berauschen“ pflegte, wird hier jedoch richtig angetönt. Der Schulbub Adolf fühlt sich im Stifte Lambach wohl, erhält hier „lauter Einser“.”

Friedrich Heer, Der Glaube des Adolf Hitler: Anatomie einer politischen Religiosität (München: Bechtle Verlag, 1968), 21.

“It was all well and good, of course, that the pope used diplomatic channels to save Jews. In the matter of genocide, however, diplomacy proved more of a weakness than a strength. Diplomacy functions within the boundaries of civilized behavior. The Holocaust ruptured those bounds beyond all measure. Hitler did not know or care to know the language of diplomacy. Pius XII’s greatest failure, both during and after the Holocaust, lay in his attempt to use a diplomatic remedy for a moral outrage.”

Michael Phayer, The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000), xii.

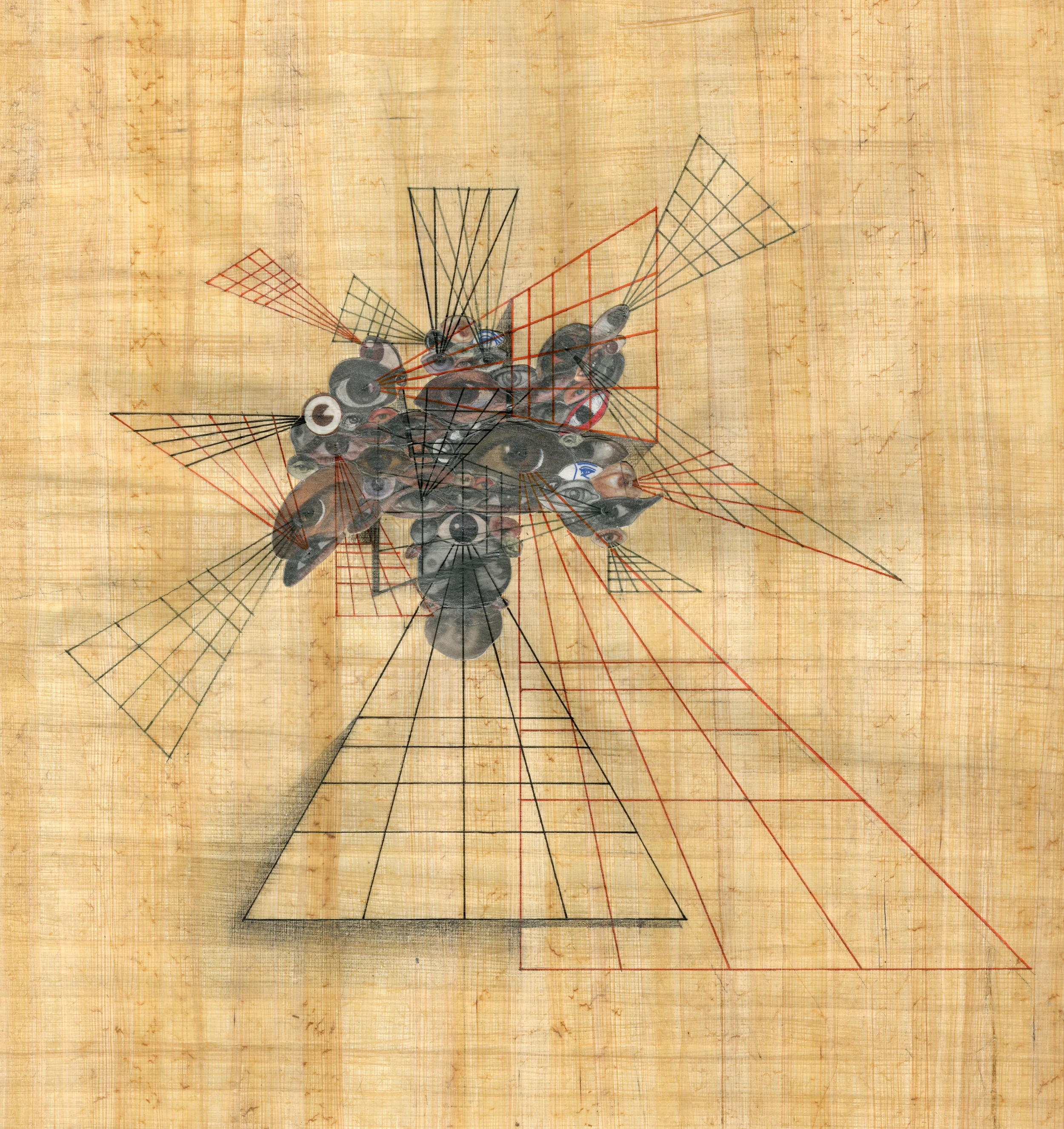

“Because the victory of the ‘Lion of Judah’ transcends all other ‘victories’ in the merely political order, the thinking allied to the ‘victory of the Lamb’ also transcends every type of thinking that emanates from a merely political order.”

Erik Peterson, “Witness to the Truth,” in Theological Tractates, ed. and trans. Michael J. Hollerich (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 166.

“‘I don’t know, Father,’ the rabbi had begun, ‘why the Church is so intent on converting the Jews. Can it suffice for her to win over perhaps two genuine believers among a thousand overambitious or feeble renegades? And then, what would happen if all the Jews in the world got baptized? Israel would vanish. And thus the only real witness to the divine revelation would vanish from the face of the earth. The Holy Scriptures would turn from a truth documented by our existence into a limp and empty myth like any Greek myth. Does the Church not see this danger? We belong together, Father, but we are not one. The Epistle to the Romans says, “The community of Christ rests upon Israel.” I am convinced that the Church will survive as long as Israel survives, but that the Church must fall if Israel falls.’”

Franz Werfel, Cella, or, The Survivors, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1989), 165.